When Bruce was Real

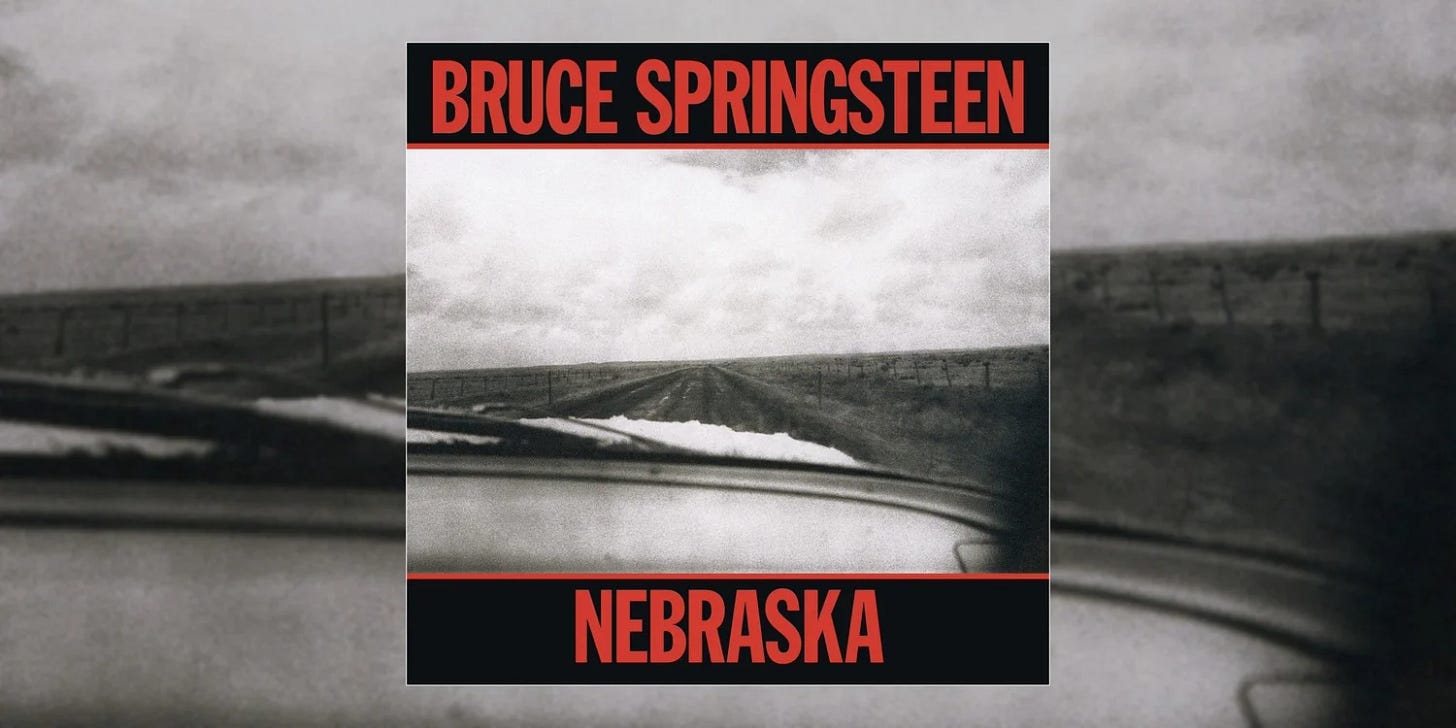

Nebraska, and Deliver Me from Nowhere

When you say the name Springsteen, you get the image of an American brand. Rugged, truthful, gritty, working class, in love with big engines and speeding cars, ready to risk it all for the thrill of feeling truly alive on Thunder Road.

Like most American brands, the image and the reality are far apart. Springsteen himself, in his Broadway show, admitted that he made the whole mythology up, because he could. As he said, “I’m that good.” Crowd applauds. But, ahh, what?! Not the embedded foot soldier in the war, but the sideline observer who then makes himself the narrator of highway songs based on others?

Springsteen never had a regular job, he was always in a band. That’s been his job all his life, and he was made for it. He first hit the scene as the neo-Dylan denizen of the Jersey boardwalk in Greetings from Asbury Park. It had powerful personal songs full of careening wordplay like “Blinded by the Light,” “For You,” “It’s Hard to be A Saint in the City,” backed by the raucous E Street Band. It was an invigorating jolt in the midst of heavy rock, the current trend. The Wild, The Innocent and the E-Street Shuffle continued in this vein, with an emphasis on the carnival lights boardwalk theme, played out in theatrical songs like “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy).” “New York City Serenade,” with its Tom Waits-ian street-wise West Side Story vibe, showed a deeper sensibility, and announced Springsteen as a major talent to be watched. In these two first records, he’s writing in an honest perspective, the observer participant, notebook in hand, the drifter romantic, telling tales of colorful characters he’s drifting along with.

Then, as with all great American brands, it exploded. “Born to Run” came out. Springsteen became an instant icon. The album was created in excruciating studio sessions, with endless layering of instruments and mixing, Springsteen was aiming for the left field rafters, and it happened, he hit it out of the park. Newsweek and Time put him on the cover the same week, “Tenth Avenue Freeze Out” was omnipresent on the radio along with “Born to Run,” and while the album was bursting with raw energy and excitement, muscular, pedal to the floor, full of verbal hyperbole, it was also overwrought and patently, well… the only honest phrase is mightily contrived. Nobody knew it at the time, of course, except perhaps Springsteen himself.

You can’t really fault him for “Born to Run.” He had his shot there in front of him, and he took it. In the music business, you might only get one shot like that. In taking it, though, he made a kind of Faustian deal. Here he was playing one of those archetypal hero guys with a hemi-powered drone screaming down the boulevard, embodying it live on stage every night. Sure, he’s a performer, and that’s always nuanced, but everybody believed the narrator of the songs was the real him. Springsteen. Bruuuuccce!!!

At the time, he didn’t have a driver’s license.

In the wake of Born to Run, Springsteen seemed to have looked into the gigantic mirror of the media and didn’t recognize himself. The next two records, Darkness at the Edge of Town and The River, had darker songs with less emphasis on cars, were more about the down-and-out, showing influences of The Grapes of Wrath and Terrence Malick’s Badlands, an influence that would show up again on Nebraska.

The core impetus of the recording of Nebraska seems to have been two-fold. In one scenario, Springsteen was making demos for the next album with the E Street Band. But, armed with an acoustic guitar, harmonica and 4 track home music recorder, he began to fall into the songs, into the landscapes, the tenuous, dark realities he was chronicling from his mind. Southern gothic writer Flannery O’Connor’s desperate characters, walking through spiritually haunted stories, influenced the record, as well as the movie Badlands, with its tale of Charlie Starkweather and his girlfriend, as told in the album’s title song.

I can't say that I'm sorry For the things that we done At least for a little while, sir Me and her, we had us some fun

Which was killing people along the way on their road trip. This isn’t the stuff of an American brand, this is actual America, as it is, as it has been. The details in the sparse song are brilliant, particularly the repeating word ‘sir’, cuing the listener that this is a police confession. It ends with these stunning lines.

They declared me unfit to live said into that great void my soul'd be hurled They want to know why I did what I did Well, sir, I guess there's just a meanness in this world

“Johnny 99” is a murder/court room song, and goes back in its roots to the traditional song “Delia,” covered by many people, notably Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan.

Curtis said to the judge, "What might be my fine?" Judge says, "Poor boy, you got ninety-nine."

We see the same repeated, with a bit of a joke thrown in, in Johnny 99.

The judge was Mean John Brown He came into the courtroom and stared poor Johnny down Well the evidence is clear, gonna let the sentence, son, fit the crime Prison for ninety-eight and a year and we'll call it even Johnny 99

Springsteen is taking up the long tradition of the bard, the singing storyteller, here. He’s a musical journalist, not the character of the song, which is the overall shift in Nebraska from previous records. The presence of the singer as storyteller rather than the actual subject of the songs is felt throughout. The masterful “Atlantic City,” which could be called the ‘hit’ off the album, tells the story of a hard-scrabble life with the relief of an escape to Atlantic City, along with the notion of rebirth and change.

Well now, everything dies, baby, that's a fact But maybe everything that dies someday comes back Put your make-up on, fix your hair up pretty And meet me tonight in Atlantic City

“Highway Patrolman” tells the story of a Highway cop with a neer-do-well brother who the patrolman let’s escape. This is a song again in the bardic tradition, telling of his long-suffering relationship with a brother who simply is bad, but who he still loves.

In “Used Cars,” Springsteen creates a Grapes of Wrath toned story of American poverty, and how people bear up under it and somehow still survive. The story hasn’t changed, the rich stay rich and the poor abide.

The sound of Nebraska is haunting, spare, Springsteen’s voice often reverbed to a ghostly degree. The songs sound like he put a chair out in deserted field at dusk and turned the tape machine on, then played into the night, with no one but himself, and maybe the crows, to hear.

The song “Open All Night” contains the line “Deliver Me from Nowhere,” which is the title of the new movie about Springsteen, about the time period when he was making Nebraska. He was apparently struggling with his identity and purpose, interested most in salvaging his musical soul. The movie was birthed from Warren Zanes’ (of Boston’s great band, The Del Fuegos) book of the same title. The subject matter is surely worthy of a movie, and the advanced reviews are strongly positive. The project was made with Springsteen’s approval, and he’s been quoted as saying he thought Nebraska was his best album.

I heartily agree. Bruce is an American treasure, the body of work is vast and varied and it can be debated endlessly where the greatness is and where it isn’t. Americans love their heroes, and Springsteen became one.

But we don’t need heroes. They all aren’t what they seem. They’re all cracked, doubting, deficient, yearning. We are, after all, just human beings. How the least of us, the poorest, the most downtrodden are treated is the true measure of us. That’s what somebody said a long time ago.

In Nebraska, Springsteen stepped off the big stage, dropped his hero badge into the dust, drove down the road and explored the reality of these crazy, compass-less, empty pocket drifters, who roam this great big land of ours, the land some proclaim to be great but don’t actually give a shit about. He looked at the real people of this country, kept down by forces beyond their ability to change, but who abide. This is who Springsteen writes and sings about in Nebraska. No heroes here, just the real thing.

Struck me kinda funny Funny yeah indeed How at the end of every hard earned day People find some reason to believe

It’s not that Badlands inspired Nebraska — it’s that the real-life Starkweather murder spree inspired both.

That was great writing. Would like to read your take on ‘Tunnel of Love’…